Migrating Floating Gardens

Migrating Floating Gardens is a sketch for a project that predicts the next location for green in urban environments. Historically, urban environments encroached upon outlying wilderness and green was detached from the city. Subsequently green was introduced first on the horizontal plane in the form of parks. Modernity and the development of dense, high-rise construction pushed green to rooftops. Currently, the vertical surface is receiving much attention as the axis for green in urban environments. As the Cartesian axes have all been heavily considered as sites for green, the logical next location lies in non-Cartesian space—floating in the air.

Gardens above Dubai

Migrating Floating Gardens is a sketch for a project that predicts the next location for green in urban environments. Historically, urban environments encroached upon outlying wilderness and green was detached from the city. Subsequently green was introduced first on the horizontal plane in the form of parks. Modernity and the development of dense, high-rise construction pushed green to rooftops. Currently, the vertical surface is receiving much attention as the axis for green in urban environments. As the Cartesian axes have all been heavily considered as sites for green, the logical next location lies in non-Cartesian space—floating in the air.

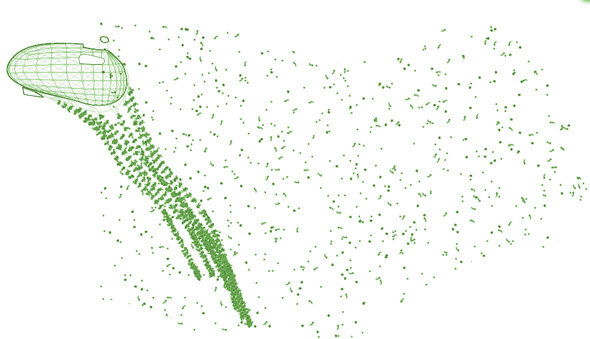

Floating gardens flocking between skyscrapers

The gardens would be suspended in the air from large remotely controlled dirigibles. Each inflatable craft would house thousands of smaller plants attached to long vines. A family of dirigibles would migrate within a city, moving towards areas where the heat island effect is greatest, and also migrate seasonally, traveling to southern cities during winter months and northern cities during summer months.

A pod of gardens

Each individual plant attached to the dirigible has attached to it a host of sensors that detect weather, traffic, pollution, noise and other urban data in real time. In addition, each plant is attached to an individual propelled device that allows it to be set free from it’s base. Controlled by GPS and GIS information and organized in flocking patterns, plants move through the city in swarms hydrating, providing shade, and bring oxygen to greenless spaces in the urban field.

Flocking green over Sao Paulo

Each pod is re-charged via its photovoltaic skin, also charging the individual plant propulsion devices. In the evening, pods return to a base within the city where they can refuel, rehydrate and recalculate the data acquired required for future aerial agricultural aggregations.

Individually propelled plants

Flocking patterns serve as a means of communication

The swarming gardens take forms that serve several purposes. In addition to the hyper responsive forms that produce shade or create new environments, advertising can fuel the gardens presence in the skies, replacing sky writing, blimps and banners pulled by airplanes, creating a more dynamic, three-dimensional and ecological aerial media.

Project Date: 2010

Project Team: Ronald Rael, Virginia San Fratello, Maricela Chan, Maya Taketani

Pruned on Migrating Floating Gardens

“One wonders if there will be an outbreak of botanical piracy, whereby someone lassos in one of the floating mobile gardens by the tentacles and anchors it right above his house all summer long, its cooling shades cutting down his air conditioner use, not to mention his electricity bill.”

Migrating Floating Gardens v2.0: Airscape Architecture

With some notable exceptions, western urban environments encroached upon outlying wilderness creating a separation between “the built environment” and “the natural environment”. This distinction eventually gave birth to a profession initially patronized by royalty, government and religious entities who held dominion over the “scape” that could be organized by the features the land had to offer. However, the invention of the term “landscape architecture” didn’t come about until 1828 and is credited to Gilbert Laing Meason, who in his book On The Landscape Architecture of the Great Painters of Italy (London, 1828) sought to define the compositional relationships between built structures sited in the landscape.1 With modernity, the aesthetic and conceptual (and expanded environmental and socio-behavioral) meshing of architecture and the landscape first considered by Meason has become increasingly blurred and the frontiers for landscape architecture are increasingly challenged by density in urban environments.

Migrating Floating Garden overhead

Extending from the landscape, “green”, which we will use as the term to refer to the carbon based and often oxygen producing inhabitants of the landscape, was primarily first introduced on the ground plane in the form of gardens and parks. Modernity and the development of dense, high-rise construction pushed green to rooftops—one of Le Corbusier’s five points—to replace the area covered by the building on the ground.2 The current demand for “greener” cities has provoked architects to seek new sites where landscape can intervene in the city. Currently, the vertical surface is receiving much attention as the axis for green in urban environments. Vertical gardens and facades that contain plant life—either as retrofit or in new construction—are the new eco-vouge, completing the triad of Cartesian axes able to be considered.

Given the exhaustion of terrestrially contiguous sites for engagement, either man-made or not, might the logical next location lie in non-Cartesian space—floating in the air? And considering Meason’s first definition of landscape architecture, can we predict that a new profession might emerge by manicuring the airscape as a new territory for exploiting the desire for greening cities? Will theories of Airscape Urbanism, like Landscape Urbanism, which postulated that landscape is a potentially superior to architecture in organizing systems in cities, supplant landscape with airscape? Migrating Floating Gardens is a sketch for a project that builds upon the prognostication that the sky is the next location for green in urban environments.

Floating gardens allow access to green in areas with poor infrastructure

Unlike the chinampas, or “floating gardens”, that surrounded the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán—immobile and anchored to lake bottom of Xochimilco—these aerial gardens would be suspended from large, remotely controlled dirigibles.3 A photovoltaic skin would power a host of sensors and transceivers that detect, record and monitor weather, traffic, pollution, noise and other urban data in real time as well as the propulsion devices that would allow the floating garden to migrate. The importance of its nomadic capabilities is a response to the fluctuating data that the garden would engage. A pod of dirigibles, for example, would migrate within a city, moving towards areas where the heat island effect is greatest, while also migrating seasonally, traveling to southern cities during winter months and northern cities during summer months to seek the most prosperous environment to maintain plant life. In the evening, pods return to a base within the city where they can refuel, rehydrate and recalculate the data acquired and required for future aerial agricultural aggregations. Reminiscent of Gilberto Esparza’s nomadic plants, the Migrating Floating Gardens could potentially move towards a contaminated river and ‘drink’ water from it. Microbial fuel cells could decompose the pollutants contained in the water converting it into energy that can feed the central processing units driving the airship.4

Each inflatable craft would house thousands of smaller low water epiphytic plants attached to long tendrils including air plants and vines. Each individual plant attached to the long tendrils has attached to it a host of sensors. These include those that detect motion, wind, light, air quality, humidity and temperature. In addition, each plant is attached to an individual propelled device that allows it to be set free from its base. Controlled by GPS and GIS information and organized in flocking patterns, plants move through the city in swarms—a “smart mob” of collective intelligence—hydrating, providing shade, increasing the local albedo and bringing oxygen to spaces devoid of green in the urban field. The swarming gardens take forms that serve several purposes. In addition to the hyper-responsive forms that produce shade or create new environments, advertising can fuel the gardens presence in the skies, replacing sky writing, blimps and banners pulled by airplanes, creating a more dynamic, three-dimensional and ecological aerial media.

Section

A more subversive post-occupancy prediction of the potential of migrating floating gardens was conceived by Alexander Trevi:

What better way to introduce invasive species; cluster bomb pollens on nature-deprived asthmatic children and, to the delight of Big Pharma, Claritin-addicted allergy sufferers; and deplete the coffers of post-econopocalypse cities by littering their streets with fallen fruits and leafy detritus for their under budgeted public works department to clean up, than with a floating mobile garden….Perhaps urban adventurers will also snag one of these gardens, but only temporarily, long enough for them to explore its feral tendrils and gelatinous parterres. They’ll emerge out of their sewers and their abandoned hospitals, and, squinting hard at the fullness of the sun, they’ll climb up, up, up, up towards the clouds, the heaviness of their claustrophobic playgrounds giving way to buoyancy and vistas.

Migrating over Manhattan

The feasibility of the project lies within a trans-disciplinary collaboration involving roboticists, horticulturists, airspace activists, airship manufacturers, swarm intelligence theorists, artificial weather scientists, to name a few, and perhaps even architects and landscape architects. When we consider other counter airscape propositions for global warming, such as dumping reflective dust into the atmosphere, or the 3,000 working satellites that dominate our spacescape, the potential for migrating floating gardens is salient and perhaps necessary. As wireless infrastructure becomes a requisite of urban life, a floating vegetative infrastructure could become a multivalent system in opposition to the fixed faux-tree cell phone towers that need to camouflage technology. Migrating Floating Gardens would not only be mobile gardens of life, but data-gardens, that finally collapse the distinction between the man-made and the natural while both navigating and organizing the city as a biological and technological ecology.

1 Gilbert, Meason Liang. On The Landscape Architecture of the Great Painters of Italy. London. Printed by D. Jaques. 1828. While Meason coined the term Landscape Architecture, Frederick Law Olmsted was the first to use the term Landscape Architect to describe his profession. See Pregill, Philip and Nancy Volkman. Landscapes in history: design and planning in the Eastern and Western traditions. New York: John Wiley & Sons. 1999.

2 Giedion, Sigfried. Space, time and architecture: the growth of a new tradition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982.

3 Adams, Richard E. W. Prehistoric Mesoamerica. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. 2005.

4 Soni, S.K. Microbes : a source of energy for 21st century. New Delhi : New India Pub. Agency, 2007.

5 See: http://pruned.blogspot.com/2010/06/floating-mobile-gardens.html

Project Date: 2010

Project Team: Ronald Rael, Virginia San Fratello, Maricela Chan, Maya Taketani

Additional Project Information: Migrating Floating Gardens v1.0 | Pruned

Migrating Floating Gardens in kerb 18

kerb 18

Migrating Floating Gardens in Utopia Forever

Utopia Forever: Visions of Architecture and Urbanism

Whether created by established architects and artists or new talents, the examples in Utopia Forever are important catalysts for fundamental change and are radically shaping our notions of life in the future. The current projects and concepts from architecture, city planning, urbanism, and art collected here point beyond the restrictions of the factual to unleash the potential of creative visions. This inspiring work explores how current challenges for architecture, mobility, and energy as well as the logistics of food consumption and waste removal can be met. The book includes Migrating Floating Gardens by Rael San Fratello Architects and text features by both architects and theorists give added insight.

Additional Project Information:

A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. —Oscar Wilde

The cities in which we live today are unfortunately not the cities that we need for a humane and sustainable tomorrow. Societies and politicians are desperately looking for solutions and ideas for the urban areas of the future. That is why the development and discussion of utopias are–next to sustainability–the most current topics in contemporary architecture.

We have learned from the 1960s and 1970s that utopian visions are one of the most important catalysts for fundamental change. Modern wind farms for generating energy, for example, were initially contemplated at that time and are now permanent fixtures in our landscapes.

Utopia Forever is a collection of current projects and concepts from architecture, city planning, urbanism, and art that point beyond the restrictions of the factual to unleash the potential of creative visions. In contrast to the largely ideal-theoretic approaches of the past, today’s utopias take the necessity for societal changes into account. The projects in this book explore how current challenges for architecture, mobility, and energy as well as the logistics of food consumption and waste removal can be met.

Whether created by established architects and artists or new talents, the projects inUtopia Forever are radically shaping our notions of life in the future.

Editors: R. Klanten, L. Feireiss

Release Date: March 2011

Format: 24 x 28 cm

Features: 256 pages, fullcolor, flexicover

ISBN: 978-3-89955-335-2

Catalog Price: €44,00 | $65,00 | £40,00